This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

This information has been archived for reference or research purposes.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page.

Military History

William Abernethy Ogilvie, Preparatory to Attack, CWM 19710261-4690, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, © Canadian War Museum

The Leadership of S.V. Radley-Walters: The Normandy Campaign ~ Part Two of Two

by Craig Leslie Mantle and Lieutenant-Colonel Larry Zaporzan

For more information on accessing this file, please visit our help page.

I don’t say that I was necessarily popular,

but I think a lot of guys who fought with me…

agreed with what I was trying to do....

~ Sydney Valpy Radley-Walters1

Introduction

For Sydney Valpy Radley-Walters, few events were more significant than the D-Day landing on 6 June 1944 and the tortuous fighting that followed on the continent. During what would prove to be a long and dangerous campaign, Rad matured quickly from a young and relatively inexperienced officer into a highly competent and respected battlefield leader. His abilities and endurance were tested repeatedly throughout the latter half of 1944 – indeed, until war’s end – yet his stolid style of leadership served as the one constant upon which he could confidently rely and upon which his soldiers could resolutely depend. It was a style influenced by his personality, his accumulated experience, his time preparing for battle, and battle itself.2 What made him an able field commander is difficult to define precisely, but the general manner in which he approached campaigning in Normandy, emphasizing, as he did, the welfare of his soldiers, battlefield innovation, and leadership from the front – among a handful of other maxims – served him and the Sherbrooke Fusilier Regiment (SFR, the 27th Armoured Regiment) extremely well, and contributed to both his and the unit’s success.

Protecting His Soldiers

Rad enjoyed commanding soldiers. He was, at times, a strict disciplinarian, as he had to be, yet sternness was also balanced by profound warmth and a strong, caring personality. He enjoyed interacting with his men, whether playing sports, instructing, or just chatting informally. When battle came, as might be expected, he continued to pay particular attention to their welfare. Although his concern at times served a somewhat cold and utilitarian purpose – he realized that those who were more content tended to fight better than those who were less so, and that he ultimately needed five men to man a tank3 he also genuinely cared for them as individuals.

The manner in which he broached psychological injuries is particularly instructive. In Normandy, when opportunity and circumstances permitted, he often sent to the rear those men who were either becoming or had already become exhausted. Given the constant pace of operations, physical and mental fatigue presented very real challenges that threatened to compromise the effectiveness of his squadron. He did not always follow the prescribed methods of evacuation in treating such casualties. In his opinion, and his experience gradually supported him in this, if a man was suffering from a slight case of battle exhaustion, he had to be removed from the front, yet kept within the unit proper. He learned quickly that men who were evacuated through the formal medical system – field ambulances, aid posts, hospitals, and the like – usually did not return to the same unit, if they returned to the front at all. Worse still, at each of these stages of evacuation, they usually encountered other soldiers who had suffered traumatic wounds, both physical and mental. Rather than expose his soldiers to such sights – sights that he thought would only worsen their feelings of helplessness and possibly lessen their already slim chances of returning to the SFR – he preferred to send them to the regiment’s rear echelon where they could rest, sleep, eat regular meals, and let the stress of battle slip away under the supervision of the regimental sergeant-major. Although removed from battle, these men still engaged in meaningful activity, constantly bringing ammunition, food, and other necessities to the front. In time, they frequently asked to be returned to normal duty, wanting to rejoin their friends who had been carrying on the fight without them. Rad believed that there was no sense in sending away good men who just required a bit of time to rest. However, soldiers who obviously required more than just a few days behind the lines were treated through the appropriate channels.4

The need to balance the welfare of his soldiers with the imperative to field an effective squadron weighed heavily. Everyone would have benefitted from being left out of battle, but it was simply not realistic to send large numbers of relatively healthy soldiers away during periods when they were needed the most. Yet, when deciding who should rest and who should remain in the field, Rad relied upon the knowledge that he had gleaned about each of his subordinates. The practice of taking a keen interest in his men was something that he had started early in his military career, and it ultimately paid dividends in many venues and circumstances. By being familiar with their individual traits, characters, and personalities, he was able to determine when something was wrong, and, by extension, how best their predicaments could be resolved. The more he knew about them, the better prepared he was to take immediate action when problems became manifest. When he did not know a soldier as well as he might have wished – which was often the case later in the campaign, given the constant casualties and resulting influx of replacements – he spoke to the most senior member of a tank crew, inquired about the condition of a man in question, and weighed the advice that he received. The close confines of a tank, and the accumulated time that the men spent together, gave each crew member unparalleled and invaluable knowledge about each other – a level of knowledge that Rad could not always achieve himself, yet one that he was more than willing to capitalize upon when required. As he commented, “...try and build up an intimate relationship with the crew commander, the person who is in command of that little group that stays in the tank, and try to find out ... just how the men are, how are they doing, and we found out …that this was terribly necessary....”5

Rad also sought to protect the welfare of his soldiers by controlling, to a certain extent, the tasks that they performed. After particularly arduous engagements, the regiment routinely salvaged damaged tanks from the battlefield in order that they might be put back in service. Those in worse condition were sometimes scavenged for parts. Much of this was grisly work, as many contained human remains in various states of recognition and dismemberment. After one particularly trying episode, in which the body of one of his soldiers was unconventionally extracted, Rad decided that, no matter how badly his squadron required tanks, his soldiers were not to concern themselves with the removal of what remained inside. He told his men soon thereafter, “…[to] just leave it alone ... just do your own business in your own tank, and that’s it, save life in your own tank, but don’t wander around trying to do other things. There’s people that are coming behind that can do all of that....”6 Here, Rad had in mind the padres, stretcher-bearers, impressed German prisoners and others who were responsible for supporting those who fought.

Rad realized that it was best to avoid handling and interring human remains. It was already hard enough to have lost one’s friends, and such activities, although necessary, only made matters worse. In his opinion, the aim was ‘to keep the fighters fighting,’ and that meant ensuring that despondency did not get the better of them. He naturally allowed them to pay respects in their own way and as a given situation best dictated – not allowing them to do so could have been equally damaging – but he generally discouraged intimacy. In this, Rad made a conscious decision to shield his soldiers from unnecessary trauma; there was already enough of that to go around. Preventing his men from participating in such gruesome activities ensured that they remained focused upon the tasks at hand. His soldiers’ mental well-being, so he reasoned, would not be well served by salvaging damaged tanks. If the regiment did the fighting, then others, for lack of a better phrase, “…could clean up the mess.”7

Radley-Walters personal collection

Radley-Walters and his tank crew, Normandy 1944.

Morale

As the squadron commander, Rad was forced to keep morale from waning, in light of the constant casualties suffered by the SFR in Normandy. Each soldier coped with injury and death in his own way, but Rad felt that he must attempt to help his men come to terms with the anxiety and despair that oftentimes resulted after costly engagements. Taking an active role, he constantly reminded his soldiers of their job, and, when the moment seemed opportune, recalled some funny incidents that involved those who had recently fallen. Some well-placed levity, balanced by appropriate and solemn respect, lifted much of the tension. Personally knowing the men under his command aided specifically in this regard, for he knew what characteristics were particular to each man that he had just lost, and, as a result, he knew where best his efforts could be placed:

I think the thing I tried to do when we lost a number of people [was to focus upon] the good things, and say ‘we lost Sergeant Snooks [a pseudonym] this morning …and you know, he was a damn good troop leader. We’re going to miss him, but some of us just [have to] carry on.’ I tried to get the conversation going that [way], you know, get people smiling again, rather [than] talking about the poor individual that had been killed. And that was [the] trend I tried to keep going all the way through. Silly to sort of say ‘keep happy,’ but basically that was the sense that we [cultivated], you know, ‘he’s too tough for most, but he’s okay with us,’ and get that attitude [going]. And you know, it worked, no question in my mind it worked....8

In this manner, Rad tried to keep his men focused upon their responsibilities. Rather than let the recent deaths continue to weigh on their minds, he offered them all some words of praise and encouragement. If he had remained aloof and uncaring, morale might have suffered. Rad did not ‘cure’ his men of their despondency simply by speaking to them in subtle tones, but, rather, his actions and words, to a degree, positively aided in their coming to terms with the now-altered reality of life in the regiment. As with much else, he was vigilant and active and availed himself of “any opportunity … of getting the men together and talking to them and … trying to impress [on] them that everything is going well.”9 Keeping his men going forward on the right path and toward the right goal required both constant attention and frequent action. He quickly realized that it was not enough simply to lead in battle. It was equally necessary to lead when out of the line, so that when the squadron returned to the front, his soldiers were as ready as they could be to continue pressing the enemy.

Integrating Replacements

With constant operations came constant casualties, and integrating replacements presented Rad with some practical leadership challenges. Through collective experience, the act of battle quickly forged his squadron into a cohesive team that fought well together. Problems arose, however, in attempting to integrate new men as seamlessly as possible without further disrupting the group’s overall synergy above and beyond that already occasioned by recent losses. To overcome this difficulty, Rad gave his replacements as much practical instruction on the ways of his squadron as time permitted. He frequently showed his new soldiers how he tended to fight his tanks so that they were at least familiar with his squadron’s basic procedures. A quick and sparse introduction it most definitely was – behind a tank, in the dark, with only rocks as teaching aids, usually on the same day that they arrived at the regiment – but with another engagement looming in the not-too-distant future, it was the best introduction that could have been realistically provided. Due to the pace of operations, Rad could provide his soldiers with only the bare minimum of instruction; a more substantive education would have to await a lull … or battle itself. In doing this, Rad was practising what to him was one of his most important leadership functions, that of providing his soldiers with as much information as possible: “...keep talking to them, in other words, passing all the tips you can whenever you can, having little groups all the time...”10

Library and Archives Canada PA-115568

A Sherbrooke Fusiliers Sherman leads soldiers of the Fusiliers Mont Royal into the streets of Falaise, 17 August 1944.

When integrating replacements into his squadron, Rad always shied away from showing favouritism. He endeavoured to treat everyone the same on a personal level, and, in this way, he hoped to gain their respect, confidence, and trust. Naturally, he singled out his most-recently-joined soldiers for extra instruction, but necessity demanded such an approach. That a handful of men might be new to the squadron did not matter much to Rad, for he immediately considered them part of the larger team – an attitude that must have been inspiring and reassuring for those on the receiving end. The need to field as many tanks as possible meant that everyone had an indispensible role to play within the squadron, and all personnel were treated accordingly. He earnestly attempted to avoid situations in which his replacements felt as if they had to work toward gaining membership in the team, as if they were second-class citizens in a one-class society. As Rad recalled:

Well, I think the big thing was don’t pick [single] out anybody … every person should be treated exactly the same whether he’s been with you for three years or he just came in yesterday, that’s what I tried to do. …now that’s not easy because [I] had people that I started with in Canada that are now in the field four years later in Normandy, and then you have the guys that just came in yesterday…. I was always fighting myself to make sure that I treated everybody equally and I think I got their confidence, because after the war was over and we’d have reunions, and so on, … they point out your bad points, your bad faults, I suppose, and the good ones, and they said, ‘you know, that’s one thing you did regardless of where the hell we came from or what we were like … you treated us all exactly the same and we appreciated it,’ so I think that was important.11

Creating the Big Picture

To further aid his replacements in their transition, and to increase their understanding of how his squadron fought, Rad tried to keep his orders simple, concise and straightforward. He reasoned that overly complicated instructions had the potential to jeopardize success by confusing a situation at hand. However, he endeavoured to give his soldiers as much information as possible concerning the situation into which they would soon be thrust. In part, Rad’s squadron was successful because of his common sense approach:

... before an operation ... you’ve got a fair idea about the outline of the operation. … To start off, get the whole friggin’ works together behind a barn or somewhere and sit down in a spot where you can talk to them and say this is what it’s going to be, and you take your time, maybe on the side you’ve got a crayon or you use whatever facilities you’ve got … and you show them, ‘and this where we are and over on the right here is going to be so and so ... and we’re going to work with these people down here …’12

Indeed, in preparation for Operation Charnwood, Rad ensured, “…[that] all Crew Comds [Commanders] were briefed the evening of 7 Jul 44. They were given the complete big picture in as much detail as possible.”13

Rad found that passing on as much information as was permitted, however it was accomplished, served a useful purpose. He tried whenever he could to inform his men of what would happen next, so that they were prepared for the upcoming operation and knew generally what to expect. By knowing the overall plan, they were better able to improvise when operations started to falter. Therefore, they were able to act appropriately and consistently without having to wait for orders. Knowing his intent, they could react to situations more intelligently and effectively than what might otherwise have been the case if they had known little or nothing overall. The better he prepared his soldiers, the better were their chances of success. As Rad observed:

… we all have to understand that we have to keep passing the information that we got initially and … keep telling the men because they’re in the dark if you don’t tell them. …in many cases the men fight their battle based on what they’re told to do, and you’ve got to keep ensuring in the back of your mind that they do understand what they’re supposed to do.14

In developing his plans for upcoming operations, Rad, true to character, always allowed his men to offer their input, since they could often add detail critical to success:

Before you ever came up with a plan, though, you made sure that if corporal so and so had been down that friggin’ road and got shot, …and he knew where certain mines were, or so and so had something to add which was very, very important to the plan that you wanted to carry out, you had to have your ears open and listen to him....15

Rad certainly was not the type to simply make plans on his own without at least asking for input from those who were responsible for carrying out those plans, and who might have valuable information to add. Despite allowing some time for questions and discussion, when it came time for his formal orders, Rad was always “…very emphatic as to what was needed at that particular time and who was to go and do so and so.”16 Ultimately, it was Rad’s orders that mattered, not the group’s opinion or consensus. Not every situation was approached in this manner, either. Sometimes there simply was no opportunity for consultation, and Rad, as the squadron commander, had to act quickly and decisively in the absence of input from his subordinates.

Orville Fisher, Tanks Passing Under a Destroyed Railway Bridge, CWM19710261-6394, Beaverbrook Collection of War Art, ©Canadian War Museum

Promotions

Battlefield promotions occurred frequently to fill the void caused by casualties. Leaders had to be replaced, and the best source of replacements was from within the regiment. The men ultimately advanced to fill vacancies generally had experience, understood the unit’s climate, proclivities, and nuances, and, perhaps most important of all, they knew the men over whom they assumed command. In these respects, they had a distinct advantage over ‘outsiders,’ men drawn from beyond the SFR to fill positions within. As the squadron commander, the responsibility for selecting suitable replacements fell upon Rad in one way or another. Owing to his rank and position, he had the authority to promote to corporal, and he often did so. The whole process was all very matter of fact:

They were promoted right there on the spot. You would call up the adjutant and say, ‘Trooper Hill is now Corporal Hill.’ That’s all you did and he put them through on orders. ... The paperwork was at a minimum and often got behind us. ... Paperwork just wasn’t that important.17

In comparison, only the Sherbrookes’ commanding officer (CO), Lieutenant-Colonel Mel Gordon, could promote to sergeant, and even higher authority from either brigade or division was required for promotions to yet-higher rank.8

Although the promotion process may have been simple in operation, Rad expended much thought and effort in selecting the men whom he believed should be advanced. He did not promote haphazardly, but, rather, he promoted or recommended those whom he thought would perform best at the next level of responsibility. Being familiar with his men gave Rad a certain degree of knowledge upon which he could base and justify his decision, but, as in dealing with casualties, he also relied heavily upon those leaders who spent a greater amount of time with the men than he did – his non-commissioned officers (NCOs). Although Rad tried to know all his soldiers personally, he was not always as well placed as his NCOs to offer an opinion upon an individual’s strengths, weaknesses, and potential. He recalled, “...so you get a hold of your top NCO, not always the sergeant-major because he wasn’t fighting, he was doing something else, and then you picked the guy....”19> By considering input from those who were most familiar with the soldiers, Rad attempted to ensure that the best and the most able were promoted, for the success of his squadron and the lives of his soldiers depended heavily upon the correct individual filling the correct position. Such exchanges required a great amount of trust between Rad and those whom he consulted.

He also considered other factors in making his selection. The input that he received from his senior NCOs and his own personal knowledge was supplemented by other factors, such as whether or not the individual had received appropriate training in England to undertake the duties that he might assume. More important, however, Rad considered how a given man had performed in battle thus far. Was he competent? Was he a good leader? Was he dependable? The answers to all of these questions, and more, influenced his final decision – a decision that was made under the pressure and duress of active operations:

... and that’s the way life is in action. You don’t have very much time to do normal things that you do in peacetime. And how can you give these guys courses [to formally qualify for their promotion]? You’ve just got to accept them because of their worth and what you believe they’re good at and promote them right there.20

Leading from the Front

A substantial amount of Rad’s time was spent in dealing with casualties and their complex aftermaths. His experience in the field certainly made him aware of the high cost of battle, yet he never shied away from situating himself squarely in the middle of it all. He understood that he had to lead from the front, setting a personal example for all to follow, and sharing the same dangers as his men. This was, he thought, the very least that they deserved and the very least that he could offer. Since they had to risk their lives, so did he. As one of his former soldiers remarked: “Rad had to be there,” and he would never ask someone to do something that he was not prepared to do himself.21 As Rad once remarked:

… you’ve got to be seen; you can’t hang back. You’ve got to be with the men. … we had some [officers] that hung back and you could tell by the resistance that came, not necessarily resistance, but no enthusiasm at all from the men. And they wanted to see their leader with them doing the things that they [were] doing and so on, and they [wanted] him up in front and…. I believe leading comes from the front, with all the chances [that] the men are taking, you’re taking the same chances that they are, and there’s where you build a confidence.22

The men expected to see their leader (or to at least know that he was present) and Rad was determined to be at the front whenever his squadron engaged the enemy. Actively participating in battle, moreover, allowed him to assess developing situations quickly, determine the next course of action, and issue orders to that effect. Given the fluidity and dynamism of each engagement, it was essential that he be able to issue immediate direction, based upon sound appreciations. Sometimes his willingness to go forward yielded other, equally important results. During Operation Atlantic, for instance, his “…personal audacious recces and those of his daring Sgt. R. Beardsley” resulted in the capture of “…enemy wireless Code Signs, complete technical data on the Panther [tank], and a mass of other valuable infm [information].”23

Regrettably, some fellow officers did not share Rad’s philosophy of leadership. One such individual that came to the SFR from another regiment proved to be a poor squadron commander, because he preferred the rear and safety to the front and danger. From Rad’s perspective:

The men hated him for the simple reason he wasn’t there. All they heard of him was on the radio, and they knew he was fairly far back and commenting, ‘Push on, push on. Number 1 troop get going! What the hell’s holding you up?’ You know you can’t do that when you’re three hills back.24

In this circumstance, a subordinate officer led the men in battle and was, for all intents and purposes, the squadron’s real leader, although the formal organization chart stated otherwise.

In order to control the battle as best he could, Rad maintained constant contact with the tanks of his squadron over the radio. His calm and collected voice not only reassured his men, but also demonstrated his presence at the front. Some of his fellow soldiers described the radio net during heated engagements as “very flat,” in which no one yelled or made others nervous. In directing the battle over the radio, Rad was methodical, precise, almost matter of fact.25 He sometimes hung back a little, in order to give himself the best perspective possible of the developing situation, but he, like his men, was very much in danger:

Radley-Walters personal collection.

Radley-Walters receiving the Distinguished Service Order from Canada’s Governor-General, Viscount Alexander, at the Bishop’s College Convocation, 20 June 1946. For leadership, tenacity and courage of the highest order. His example has been an inspiration to, not only his junior officers and senior non-commissioned officers, but to every man in his squadron.

… the big thing is control by talking to them on the wireless, keep talking to them. In other words, don’t just have a lull and nobody hears anything, just keep calling … ‘hello one, and move now about 200 yards to your right’ and so on, ‘okay, number three, one is moving over there, you support him’ and so on, ‘start firing now’ and such. In other words, get them into the whole business of covering one another as you’re moving ... and you’re heard if you’re on a squadron or a regimental net, everybody hears you, every tank, so they understand what the action is and what you’re doing in fighting it. You just don’t go banging off across the country with nobody talking to you.26

Innovation

Although Rad had a knack for interacting with people, his abilities did not end there. To be sure, he was also possessed of great technical aptitude and the ability to think ‘outside the box.’ The campaign in Normandy presented a number of novel difficulties, yet he devised both innovative and effective solutions, sometimes on his own, and sometimes in cooperation with others. Rad constantly demonstrated a profound ability and willingness to innovate, or, at the very least, to borrow solutions from others that had proven effective. He endeavoured to learn as much from his surroundings as he could – other soldiers, his own experience, and available publications – and to adapt these lessons to his own particular situation. Possessing an active mind, developed in childhood through an emphasis upon education, he was never content to leave something the way it was if a better way could be found. The status quo was certainly not unassailable.

Rad constantly made a point, whenever the time and opportunity presented themselves, to discuss his technical problems with men from other regiments in order that knowledge and ideas might be shared. He tried not to be closed-minded, for he seized upon each meeting to learn from others. The solution to a common challenge was often found simply through frank and honest discussion: “You know, we became great friends. …we’d get together, not frequently, but the odd time that we could get together, and sit down and talk to one another about our particular experiences, and we learned a great deal from one another that way.”27 And certainly, there was some pressure to innovate. Like other armoured regiments at the front, the Sherbrookes lost a considerable number of tanks to their technically-superior foe. Realizing that the German machines often outclassed his own, Rad attempted to make the Sherman less vulnerable by adding additional “armour.” As with much else, he shared his ‘solution’ with his brother officers who were likewise suffering high casualty rates:

Well, we [the SFR] and the Fort Garry Horse and the 1st Hussars, we’d have little discussions whenever we came out of action sometimes, and they said, ‘What are you doing Rad?’ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘we’re working at night, where tanks are knocked out and so on, and taking the tracks off and we’re breaking the tracks, some of us are using two and three tracks together and welding that on, and some of us are cutting it right down to one pad, and [adding it] in certain areas and so on around the turret and on the flanks and so on.’ …our vehicle mechanics … poor devils, not only were they keeping us going in the daytime, but at night they were out there … cutting up track and so on and [they] welded this on in a particular pattern. …sure I’ve been hit with the thing [a German round fired from a tank] and all my tracks flew in the air, but the bloody tank lived and that to us was the important thing.28

In the end, the added armour – pieces of track spot-welded in place at various angles so that they would “give” when hit – not only made the tank less vulnerable to German fire, thus increasing its lifespan and usefulness on the battlefield, but it also saved the lives of many crewmembers.29 In this, as with much else, Rad was guided by the simple truism that “tanks could be replaced, men could not.” All of this was done ‘on the spot,’ under his own initiative. Rather than waiting for a solution to be found elsewhere and to be disseminated throughout the armoured corps, he developed his own remedies, demonstrating his willingness to seize the initiative and to innovate when the situation demanded. The sharing of information between units was extremely important to Rad, for such a process allowed him to capitalize upon the expertise that resided outside his own squadron and regiment, while, in turn, others could benefit from his insights and suggestions. “So there were lots of little hints, not hints, but good points, [which] were being made by just getting your experience from somebody else who has gone through it, who passes it down to you.”30

Library and Archives Canada PA-114966

The Sherbrooke Fusiliers enter Xanten, Germany, 7 March 1945. The additional armour protection on the tank’s hull is readily apparent.

Such was not to be the last time that Rad was forced to innovate in the hopes of prolonging the service of his beloved tanks, and, as well, of saving the lives of the men inside. Because the floor of the Sherman was thin, he realized that sandbags placed in the bottom of the crew compartment would absorb much of the blast caused by anti-tank mines.31 He recalls:

The bottom of that Sherman tank is ... thin, and Christ, we’ve got armour all over the outside ... but the bottom was very thin. We started losing tanks on mines,…so we made a long sandbag … it wasn’t a bumpy thing, you could move it in around…. And you know, that helped a great deal when a Teller mine, or a couple of Teller mines, went off, and [the sandbags] saved them.32

As before, Rad identified a problem and did the best that he could to overcome it with the resources on hand. His solutions were not always complicated, yet they were effective, and that was what mattered most.

Rad mastered the armoured soldier’s art after D-Day, but his expertise extended to other arms of the service as well. Having been introduced to the army through the artillery in the late 1930s and early 1940s – the Canadian Officers Training Corps at Bishop’s was affiliated with a Sherbrooke-based artillery battery – he took a keen interest in this branch when in Normandy, appreciating its power, potential, and usefulness. After a few battles, he realized that the artillery could be the decisive factor in an engagement, and for this reason he learned all that he could about how this branch operated, its constraints, how he could communicate with them, and any other piece of information he thought useful. His days at university gave him a good, fundamental understanding, but, in Normandy, he sought further detail to complete his working knowledge. On many occasions, Rad had lost the use of the artillery when his Forward Observation Officer (FOO), the man responsible for bringing down the guns on a particular target, became a casualty. Not content to be robbed of such an invaluable tool, he learned how to call the fall of shot himself, essentially acting as his own FOO. Once he understood how he could work with the artillery, he regularly used the guns to assist with the regiment’s work:

I speak to a number of people [these days] and they never used that [artillery and air support]. I thought, ‘God, that’s strange.’ It just seemed to come to me that there’s the artillery, why don’t you learn about that artillery? I’m not an artilleryman, but I bloody well learned and I could be a forward observation officer for the artillery the same as a man who was trained to do only that particular job. And the same thing with respect to bringing in ‘air.’ We hadn’t been taught in England very much about an air contact team to be able to speak to the aircraft, but it’s a skill that you have to learn, and in action is not the place to learn it.33

The same could also be said about Rad’s use of smoke to blind the Germans to the Sherbrookes’ movements. The SFR received no instruction in England on this score, but as soon as he landed in France and appreciated just how cloudy the battlefield could become, he immediately took it upon himself to learn how to employ smokescreens. As he recalled:

… and the other thing is educating yourself… I think you just keep educating yourself. The more I think of every time we went into action, we came out having learned something that we didn’t know before, [such as], the use of smoke on the battlefield. None of us knew anything about it, so we had to learn it. Where did we learn it? We learned it on the battlefield. Some of us continued on and picked it up and did quite well at it....34

In nearly every engagement after D-Day, Rad made copious use of smoke, not only to give his squadron an advantage over the enemy, but also to afford his own soldiers a degree of added protection. So convinced was he of its usefulness that he concluded after Operation Atlantic: “The practical use of smoke must never be forgotten particularly in attack. A sqn [squadron] shoot of smoke produces a most effective screen. Serious consideration to the installing of rear emission smoke on tks [tanks] should be considered.”35

His willingness to learn and employ the trade of others, it seems fair to say, made him more successful than what he might otherwise have been. The fact that he could fight his tanks well, even brilliantly, bring the artillery to bear when needed, hide his movements from the enemy, and support the infantry, by placing a SFR officer with the infantry and putting an infantry officer in a tank, made him a formidable leader in battle.36 His earlier experiences with the artillery, while a member of the COTC, and the infantry, prior to the SFR’s conversation to armour, made him familiar with the limitations and possibilities of each arm, valuable knowledge that he supplemented and used to great effect in Normandy.

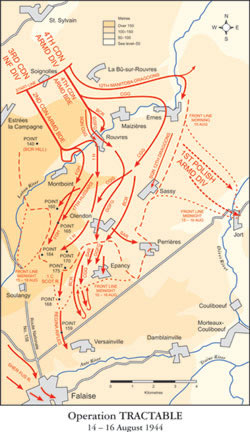

Map by Christopher Johnson

Operation Tractable, one of the most significant and dynamic combat engagements of the Normandy campaign.

Every Man Has His Limits – Rest in England

As the fighting continued in Normandy throughout the summer of 1944, the physical and mental strain of constant, high-intensity operations began to take its toll on young Rad, and his behaviour changed appreciably. Always aggressive and confident, he became even more willing and anxious to engage the enemy, so much so that he started taking chances with his life, and, by association, the lives of his men, that were not always prudent. Rather than withdrawing from the perils and stress of battle, as others were wont to do when under similar stress, he actively sought additional opportunities to use his now-refined skills:

... I found that ... other people who were in my squadron close to me ... were getting tired and I reacted the opposite. I thought the Germans had their guns crooked. I really believed that there wasn’t a gun on the German side that could knock us out. We just went the other way, felt , ‘…give me anybody’s task, and we’ll do it and we’ll do it well.’ In other words, asking for more competition and everything....37

Rad’s changed personality, his disregard for danger, and his belief in his own invincibility did not go unnoticed. Mel Gordon soon recognized that one of his most experienced and able officers was acting erratically, and, as a result, Rad was sent back to England for a well-deserved and much-needed rest. From the time that he landed on the beaches to the time that he left the battlefield, albeit temporarily, he had seen some 80 days of continuous action, witnessed horrific casualties, had participated in a number of major battles, and had assumed ever-increasing responsibilities.38 Constant activity of this type came at a cost, and it was only with time that it began to express itself.

While in England, at a Canadian Armoured Corps Reinforcement Unit, Rad taught others the lessons that he had learned through hard experience in France. He was, in essence, fulfilling one of the responsibilities that he held so dear – namely, passing information to others who would later benefit from it. The pace of life in England was hectic – the need to quickly train adequate replacements for the front was always a pressing concern – but not being burdened by the same amount of responsibility or stress was pure pleasure, and he enjoyed every moment. Being removed from the battlefield, Rad took time to pause and reinvigorate both his mind and soul in preparation for his eventual return to the SFR at the front, which occurred some weeks later. The Normandy campaign was over when he resumed his command, but many more months of fighting lay ahead in both The Netherlands and Germany. By this time, however, having been the beneficiary of so many formative experiences, Rad’s leadership style had more or less emerged in full and would continue to prove successful until war’s end. Rad continued to learn from his later experiences – his driving personality would not have it any other way – but by the end of the Normandy campaign, he clearly understood both the technical aspects of fighting his squadron and the psychological aspects of leading his men.

Radley-Walters personal collection

Radley-Walters in the uniform of a post-war brigadier in the pre-Unification Canadian Army.

Conclusion

Rad stopped short of calling himself a ‘popular’ leader in one interview, yet he was highly respected and well-liked by those who served with him.39 Some of his fellow soldiers remarked that they would have “followed him down the barrel of a gun,” because “…we thought he could do anything.”40 Praise for his accomplishments came from all quarters. When he returned to Canada after war’s end, one local newspaper commented: “The stories of his wonderful leadership and personal bravery have become legends in the unit, and his record of personally knocking out eighteen German tanks is believed to be the highest of any Canadian officer.”41 Rad’s reputation has only increased over time since the Second World War.

Much of this esteem for and confidence in his abilities as a leader came from his particular style of leadership that struck an intimate balance between accomplishing the mission and, at the same time, caring for his soldiers. His ability to lead well both on and off the battlefield stemmed from his professional competence, something that he always strove to improve, and the respect that he held for all, something that he always tried to demonstrate. Many of his leadership traits developed early in his career, as a young officer fresh from university, yet others required the actual trial of battle to emerge. In the end, he may not have done everything right, but it certainly seems that he was correct more often than not.

Rad approached his job seriously. He understood what needed to be done and sought the means that would accomplish these ends, whether he had to invent them himself, borrow them from others, or rely upon his own soldiers to suggest what should be done. Dealing with casualties, integrating replacements, overcoming technological deficiencies, among sundry other challenges, required an active hand, and, in many cases, novel solutions. For him, leadership was a human game in which the constant interplay between actors, and the relationships that developed, were influenced by situation and personalities. In the end, it is only appropriate that the final words here are his: “The biggest lesson I think I learnt during the war is that if you are willing to lead them and lead them well, they’ll never let you down....”42

We should like to thank the following individuals for their kind assistance at all stages of this project, for without their support and encouragement, little could have been accomplished: Jeff Stouffer, Pat Radley-Walters, Bill Coupland, Wyn van der Schee, Andrew, Harvey and Irene Theobald, Douglas Hope, Alf Hebbes, Paul Pellerin, Tim Cook, Bob Edwards and Bernd Horn.

Radley-Walters personal collection

Pat and Rad in retirement.

![]()

Craig Leslie Mantle is a Research Officer with the Canadian Forces Leadership Institute at the Canadian Defence Academy in Kingston. He is also a PhD candidate studying under the supervision of Dr. David Bercuson at the University of Calgary.

Lieutenant-Colonel Larry Zaporzan, an armoured officer and a former Commanding Officer of the 8th Canadian Hussars (Princess Louise’s), is currently the Assistant Canadian Forces Military Attaché in Washington.Notes

- C.L. Mantle interview with S.V. Radley-Walters, 21 August 2007. All interviews were conducted at Rad’s personal residence in Kingston, Ontario.

- A discussion of Rad’s initial leadership experiences, from the time that he joined the Canadian Army to the eve of the Normandy invasion, can be found in the previous volume (Vol. 9, No. 3) of the Canadian Military Journal.

- Commander, Driver, Co-Driver, Loader / Operator, Gunner.

- Mantle interviews with Radley-Walters, 31 January 2007 and 7 March 2007. For further information concerning stress casualties and their treatment, see A.D. English, “Leadership and Operational Stress in the Canadian Forces,” Canadian Military Journal, Vol. 1, No. 3 (Autumn 2000), pp. 33-38, and Terry Copp and Bill McAndrew, Battle Exhaustion: Soldiers and Psychiatrists in the Canadian Army, 1939-1945 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990).

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 7 March 2007.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 11 April 2007.

- If Rad protected his soldiers from some of the gruesome realities of war, he also protected them from meddling, ill-informed officers. After one particularly trying battle, for instance, a gunner began changing the co-axial machine gun on one of the tanks in Rad’s squadron, as the constant firing had all but ruined the barrel. At this time, an officer happened to walk by, whereupon he told the gunner that the gun seemed fine and that it could still be used. Being within earshot of this exchange, Rad informed the officer, politely, but with enough force and emphasis to make his position more than clear, that if the gunner said that it was “burnt out,” then it was “burnt out,” and that it was probably best not to tell his men how to do their job, especially since they had been fighting since landing on Juno Beach in early June. Rad’s actions – placing his trust in his soldiers and supporting them against authority – were, in the opinion of one of his subordinates, “very heartening.” Rad “knew when people were right” and supported them as best as he could. It is not entirely clear if this episode occurred in Normandy or after the campaign’s conclusion. Thus, it has been included in the Notes, rather than in the main text. Nevertheless, it provides further insight into Rad’s personality and style. C.L. Mantle group interview with Alf Hebbes, Jimmy Jones, Ed Haddon, Alf Hall, Weldon Clark, Arnold Boyd, Phil Lawrence and John Hale at the Sherbrooke Fusilier Regiment’s monthly reunion, Royal Canadian Legion Branch 344, Toronto, Ontario, 27 November 2008. [Hereinafter, Group Interview.]

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 11 April 2007.

- Ibid.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 31 January 2007. During the war, and throughout his entire military career, Rad always tried to pass to others the knowledge that he had gained. In this, he was following the advice of his mentor, General F.F. Worthington, who always taught, “…[that] one of the most important things in your profession, in leading, is the ability to pass it on, you know.’ He said, ‘just pass it on, tell the guys.’ He said, ‘if nobody tells them … they’ll never know, poor devils, so tell them, keep telling them and keep repeating it,’ and I think that’s so true, and I tried then to follow his example….” Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 11 April 2007.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 4 April 2007.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 7 March 2007.

- em>Library and Archives Canada [LAC], M.B.K. Gordon Fonds, MG30-E367, Vol. 2, Folder 18, “Op ‘Charnwood’ The Fall of Caen – 8/9 Jul 44,” 17 Jul 44, p. 11.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 6 December 2006.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 15 November 2006.

- Ibid.

- Lawrence James Zaporzan, “Rad’s War: A Biographical Study of Sydney Valpy Radley-Walters from Mobilization to the End of the Normandy Campaign, 1944” (Unpublished MA Thesis, University of New Brunswick, 2001), p. 184.

- Ibid.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 15 November 2006.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 6 December 2006.

- Group Interview.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 6 December 2006.

- LAC, Gordon Fonds, Vol. 2, Folder 18, “Op ‘Atlantic’ – Overture to the Breakthrough,” 31 Jul 44, p. 8.

- Zaporzan, p. 223. Rad observed that the men nicknamed this officer “Three Hills Back” given his propensity to remain well away from the front.

- Group Interview.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 21 February 2007.

- ; Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 4 April 2007.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 11 April 2007.

- See LAC, Gordon Fonds, Vol. 2, Folder 18, “Op ‘Atlantic’ – Overture to the Breakthrough,” 31 Jul 44, p. 15, where evidence is to be found of such added armour saving a “C” Squadron tank. For further evidence of the same, see Blake Heathcote, Testaments of Honour: Personal Histories of Canada’s War Veterans (Toronto: Doubleday, 2002), p. 307.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 4 April 2007.

- It is not asserted here that Rad was the first to employ such a solution. All that can be said is that he used this approach, regardless of whether he developed it himself or borrowed it from somewhere else.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 11 April 2007.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 31 January 2007.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 21 February 2007.

- LAC, Gordon Fonds, Vol. 2, Folder 18, “Op ‘Atlantic’ – Overture to the Breakthrough,” p. 12.

- A discussion of infantry-armour cooperation, and Rad’s role in facilitating the work of the two in battle, was conducted in Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 6 December 2006.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 29 August 2007.

- Soon after landing in France, Rad, a captain in “C” Squadron, was promoted to acting major and transferred to “A” Squadron to replace the latter’s commander, E.W.L. Arnold, who had been evacuated to hospital with battle exhaustion. See Zaporzan, pp. 157-159.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 21 August 2007.

- Group Interview.

- Sherbrooke Daily Record, “Welcome Home” edition, circa 2 February 1946, p. 3.

- Mantle interview with Radley-Walters, 31 January 2007.